"The odd thing was....that it was our own men that I was afraid of. It didn't occur to me that the skraelings would change their mood, or suddenly attack. I knew nothing of their nature, but I knew my own people very well, and I knew they couldn't be trusted to keep the peace."

The Sea Road

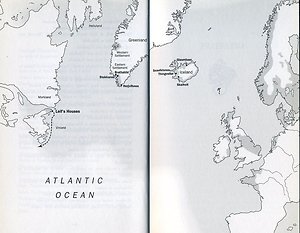

Map of The Sea Road | Publication details | Reviews

I saw my notebooks for The Sea Road again when I took a workshop at the National Library of Scotland, which now holds my archive. It was odd to handle my own sea-stained, coffee-ringed jottings in the controlled atmosphere surrounding original manuscripts.

I’d written them in the early 1990s while travelling on the cheap in Iceland, Greenland, Labrador and Newfoundland. I wrote much of The Sea Road longhand, in my tent or in hostels, cafés and libraries. In summer they let - or used to let - travellers sleep in the empty primary schools. I was staying alone in a school at Stykkisholmur, on Snaefelsnes (right).

As I lay on the schoolroom floor in my sleeping bag, in the light night, I looked at the paintings on the wall. The children had been doing a project on Gudrid, a real historical character, who appears in Eirik’s Saga and Greenland Saga. The story of her life was set out in the pictures that surrounded me.

And so I encountered my next novel.

Over the next three summers, I followed Gudrid’s travels. See the map below. Her story begins with her early years at Laugarbrekka, between the sea and the lava fields, dominated by Stapafel rising behind, and beyond it snow-covered Snaefel (left). As told in the sagas, we have the external details of Gudrid’s life (not always consistent) but we aren’t told what she thinks and feels. That’s not what the saga narratives are about. I decided that, in my version, she would tell her own story.

As a young woman, Gudrid accompanied her father from Iceland to Greenland. After a terrible sea journey they arrived at Eirik the Red’s farm at Brattahli∂, on Eiriksfjord. Later, with her first husband, Gudrid went on a fateful journey to visit their farm at Sandnes, on the west coast of Greenland. I was able to follow her voyage to Sandnes in the coastal ferry boat, from modern Quqortoq to Nuuk. With her second husband, Thorfinn Karlsefni, Gudrid sailed from Brattahli∂ to Leif’s Houses (now L’Anse Aux Meadowes, Newfoundland). I’d hoped to do the same, but there were no boats.

Gudrid sailed on from Leif’s Houses into the heart of Vinland. The sagas describe the place called Hop, an enclosed lagoon where the ships could be pulled up for winter. Finally, Gudrid came home to Iceland. She and Karlsefni lived on his farm in the north at Glaumbaer, where she is commemorated with a statue (right).

At the end of her life Gudrid went on a pilgrimage to Rome, and my rationale for her narrative is that she is telling her story to a young Icelandic monk, Agnar, during her sojourn there. Agnar, her amanuensis, is a fiction. He parts from Gudrid on the shores of Lago Bracciano, as she sets off on her long journey back to Iceland. I too parted from Gudrid on the shores of Lago Bracciano. Agnar was very sad to say farewell to her, and so was I.

I first came to Iceland in 1991, helped by a travel grant from the Scottish Arts Council. I’d wanted to go to Iceland all the years I’d been in Shetland. I’d been to Faroe; Iceland was the next step, tantalisingly far to the north-west, but central to the Norse Atlantic story.

I found a country that seemed raw and new; the rocks at home in Scotland, hardened lava or worn by ice, told the same story but so long ago it didn’t seem to matter any more. Here, it was still happening. I’d never seen such shapes and colours. Walking across the black ash of Maellifellsandur, or the ochre and red rhyolite, bare of vegetation, or the glaciers cracked open like nuts to reveal blue depths, or feeling the heat through my boots on the cooling lava of Eldfell on Heimaey, or brushing through willow and birch waist-high, it was like walking in a place I’d always dreamed about. I felt like I’d known it all the time, and yet it was so unlike anywhere else I’d ever been.

Hitchhiking around Iceland, more than once it was the Penguin edition of a saga that found me friends. I’d be sitting by the empty roadside reading, and stick my thumb out when a car came: “You’re reading Laxdaela Saga! We’ll take you to the very bend in the river where Hoskuld overheard Melkorka talking to little Olaf! We’ll drop you at Hvamm, where Snorri Sturluson was born, and also my wife, 700 years later…”

At Bergthorskvoll, where Njal’s house was burned, I was dropped off by a lorry, and I found a woman digging in her garden. I tried to say in Icelandic, “Is this Njal’s house?” “Oh yes", she said [in English]. "Here was the house. Behind that mound, hid Flosi and the Burners. There is Đrihyrningur Peak, and that’s the way the Burners rode across the plain.” She made it sound like it had happened a week ago.

I found a home from home in Iceland with Agnar and Hlif, who farmed at Krisakot, on the north coast (right). Seeing Agnar with his cattle, in spite of the modern byre and milking apparatus, took me back 1000 years - this is an easy step to take in Iceland.

Hlif was descended from Aud the Deep-Minded, one of the original settlers of Iceland. Agnar was determined I should understand Icelandic literature. One day he sat me down with Njala Saga in my hand, and a recording in Old Icelandic on the tape recorder. “You must hear it,” he said to me. “You must hear it.” And, because I knew the story, and had the Norse words in front of me, I somehow could hear it. After 23 years, I visited Agnar and Hlif again. Agnar had written a poem to me, with a formal Skaldic rhyme scheme. I treasure it better than I can read it.

In the Seaman’s Mission at Quqortoq, Greenland, the cafe staff asked me if it was my diary I was always writing at the table by the window, or a book.

At Brattahli∂, I sat on the doorstep of Eirik the Red’s house (right) and drew a little sketch of what I could see. Very little had to be changed when I put the sketch into Gudrid’s words, as she sat on that same doorstep 1000 years earlier.

The Danish curator of the museum at Narsassuaq (Gudrid’s Stokanes) said to me, “It’s better if I show you the Norse sites directly.” He took me in his boat round Eiriksfjord, and we landed at one site after another. There were the remains of the longhouses - house and byre together, and nearby the boatsheds and the milking ring. Beyond the ruins nothing had changed at all.

The following year I travelled from St John’s to L’Anse Aux Meadowes, Newfoundland, with my aunt, by that time 35 years a Newfoundlander, and everywhere we went people came out of their houses, saying, “Is that Dr Elphinstone? 30 years ago you saved the life of/ got treatment for/ cured my child/mother/brother etc.” Aunt Norah was a passport to every outport on the coast of the Northern Peninsula and Labrador.

At L’Anse aux Meadowes (right & below), she wandered round the marshes botanising, while I studied the site and made notes. We crossed on the ferry to Labrador among huge lorries and drove her little car as far as Red Bay, where the dirt road stops, and where I bought the handmade patchwork quilt, which still covers my bed, from our B&B landlady.

Ironically, as The Sea Road has sold best of all my books, it was tossed around in the rough waters of publishing for a while before it came to safe harbour. When I left for America in 1996 I left it sitting in a drawer. I returned much refreshed, and sent it to Canongate. Jamie Byng accepted it almost immediately, and gave me a two-book contract for The Sea Road and Hy Brasil. I am happy to say I have remained with Canongate ever since. I got a prize for The Sea Road which has allowed people with limited adjectival ability to apply the word ‘prizewinning’ to it - or rather to me - ever since. The original title was ‘Gudrid’s Story’, but Canongate wanted me to change that. To me it is always Gudrid’s story. That is what all those journeys were about. I was steeped in her story and her world. Nothing since has added to that, or taken any of that away.

Publication details

Published by Canongate, Edinburgh 2000. 244pp

ISBN 1841950513

Buy The Sea Road

This book has been published in Canada:

McArthur and Co. Toronto. 2000, 2nd ed. 2001. 244 pp.

Translated into German by Marion Balkenhol as Der Weg Nach Vinland

Germany: Econ Ullstein List Verlag. 2001. 336 pp.

Translated into Danish by Lene Gulløv as Søvejen

Copenhagen: Lindhardt and Ringhof. 2001. 254 pp.

Translated into Portuguese by Alice Silva Santos as

O Caminho Maritimo Lisbon: Lyon 2003. 254 pp.

The Sea Road was awarded the Scottish Arts Council Spring Book Award for 2001

The Sea Road appears in '100 Best Scottish Books of All Time' produced by List Magazine

Reviews of The Sea Road

The Times | TLS | The Herald | The Historical Novel Soc. | The Bookseller | The List | Globe & Mail(Toronto)

"Gudrid of Iceland was the farthest travelled woman in the world during the Viking Age, from Iceland and Norway to Greenland and North America and then to Rome. She gave birth to the first European child born in North America and for a thousand years she has deserved a saga in her own right.

"Margaret Elphinstone has made good the omission at last – and how well she has done it!"

Magnus Magnusson

Times Literary Supplement

"The Sea Road describes with great vividness the routines, the discomforts and the occasional glories of life on a longship, ashore in Iceland and its dependencies, Greenland and Vinland. There is a pleasant scene when the monk delights Gudrid – who is illiterate, of course – by showing her an illuminated bible."

Ron Kirke

The Times

"Forget Richard Branson, the audacious female traveller Gudrid of Iceland is the original explorer’s explorer … Elphinstone has written a fine tribute to a woman whose tale is as warm and inviting as a hot spring on a clear winter day."

Alex O’Connell

The Herald

"… One of the many beauties of this novel is the way in which Elphinstone puts flesh on old saga bones. While much of the dialogue is fittingly laconic, there are delightful passages of lyrical prose which describe isolated pockets of beauty among the frozen desolation of Greenland … Every other page, it seems, is gilded with erudite detail, bringing the saga templates to life … As well as capitalising on the narrative verve of the sagas, Elphinstone has intellectualised her source material deeply … The result is a novel which is wonderfully rich in ideas of real philosophical depth.

"My feeling is that our writers of late have over-indulged in gritty, modern, urban Scotland. It’s a refreshing delight to read a novel of such extremely high calibre which interweaves mythical, magical, and historical dimensions in ways which are reminiscent of the Scottish Renaissance literature of the twenties and thirties. Elphinstone is a worthy successor to writes like Linklater and Mackay Brown, developing their themes in the new century with a voice which is distinctively her own. Never before has the Norse past been put to such evocative and compelling use in our literature."

Simon Hall

Historical Novel Society

"So many historical novels are peopled with modern thinkers in period costume, but not The Sea Road. All the characters are completely of their time and their era is absolutely convincing. Their thoughts and actions have such a ring of truth that a keen sense of realism is maintained throughout."

The Bookseller

"… a gripping historical novel … The Sea Road is firmly founded on the old Icelandic sagas and written with considerable style."

Peter Donaldson

The List

"Gudrid is a great guide and her storytelling skills are second to none. Her Viking men are almost superhuman, her landscapes pure and her understanding of the ultimate sense of ambition that powers every generation is often startling. Forget Seamus Heaney’s new adaptation of Beowulf, this is much more fun."

Paul Dale

The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

"Elphinstone is a canny, graceful writer whose prose is as clear and clean as Greenland air… This is historical fiction at its best, and the quality of Elphinstone’s prose shines from every page."

Joan Clark